OK, so full disclosure: I’m a crier. I snivel at the drop of a happy or a sad ending. I tear up at feats of astonishing human achievement, bravery, loyalty, courage, against-the-odds survival, redemption, etc. Thinking about it, I tear up at astonishing feats of animal bravery, loyalty, courage, and against-the-odds survival. Not sure if redemption is a thing for animals, although there are some fantastic stories of animals that have gone feral and been rehabilitated, which have the same effect.

Perhaps a better way of putting it is that I am easily moved. I hope that means I’m healthily plugged into my emotions, not just at the mercy of a heap of repressed crap that gets triggered by the stuff I see, read and listen to. In any case, our experiences, good and bad, shape our responses, whether they bring smiles, laughter, tears or even a whopping great punch-up—some are just more in more socially acceptable than others. I’ve written a lot about the benefits smiling and laughing with, or even at, others, but a good cry is up there in the feel good stakes too.

According to Dr Thomas Dixon, in a recent book where he examines the history of British Crying — Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears (don’t you love the title?), “Weeping is an intellectual activity, and yet it is also a bodily function like vomiting or sweating, or farting.” Tears seem to fulfil a higher function than just a vulgar bodily emission, but I guess they’re all forms of purging. When you think about it, crying’s not just an eruption of our emotional geysers, they’re also a way of protecting our eyes from spoilers like onions, billowing smoke, and particles carried in the wind by washing them out.

Whatever. There’s nothing like a good cry, or, as my Scottish compatriots would say, “a guid greet”. We have a rich vocabulary around crying. Snivelling, tearful, blubbing, wailing, sobbing, weeping, howling, bawling, to name the ones that instantly spring to mind. Bit like Miss Smilla and all those words for snow. Given how essential it is to our wellbeing, it’s a pity that publicly crying is one of the last taboos of our era. It’s almost up there with PDA (public displays of affection) on the pantheon of awful. We make fun of outsize emotions. God help the celeb caught crying a river over a broken relationship — paps have a field day, and it’s nirvana for the wits of the world who conjure meme magic to the schadenfreudistic (is that a word?) delight of all.

It hasn’t always been like this. We’re much more buttoned up than we used to be. From the earliest of times, tears have been associated with mourning rituals that included extreme acting out—prostration, excessive crying, tearing the hair, ripping clothes, smearing ashes on your face, for example. I’m glad that style of mourning has … er … died a death. But we’re far from it being considered good form to break down sobbing if our cappuccino is delivered cold.

In the medieval and Tudor world, histrionics were all the rage. People regularly gave their lachrymal glands a workout. Think big beefy Henry VIII (in his later years) projectile crying and generally carrying on like a toddler in full view of his court when something didn’t go his way. Up to comparatively recently, crying and emoting bit time were social norms. In the grip of high Romanticism, the early Victorian ear was awash … literally. It wasn’t until Albert died, leaving Victoria a grieving widow, that the vibe changed and emotional exuberance exited stage left. In it’s place came the stuffy, straight-laced, stiff-upper-lipped society we associate with the later era (at least on the surface). And it happened in only a couple of decades. Thanks for your legacy, late Victorians!

Subsequent generations copped all those repressive sentiments like “big boys don’t cry” and “I’ll give you something to cry about”. Even now, with much more relaxed standards and our buy into the concept of emotional intelligence, we’re not performative in our grief like our forebears.

The Tearjerker movie was a genius invention in a world with so little tolerance for adult tears. Tearjerkers allowed us a legitimate release valve. We could snivel up a storm in a dark auditorium where the tear police’s writ didn’t run. Of course, penance for this self-indulgence came in that ghastly moment when you had to exit your local Odeon clutching a wad of soggy tissues with bloodshot, morning-after panda eyes, and mascara-streaked cheeks. A blobby red nose and puffed-up, swollen lips completed the wrung-out look. The fact that everyone emerged the same did nothing to diminish the cringe factor of being seen having given in to an emotional storm. You could even hear the most blokey blokes coughing manfully, trying to camouflage this heinous crime. No one met anyone else’s eyes. It was wonderful and embarrassing and deeply cathartic. There is nothing like a good cry.

I read an article this week about the absence of tearjerkers from our screens over the last couple of decades. Perhaps, with the advent of streaming services, we no longer saw the attraction of collective emoting in the dark. It’s just not the same sitting at home blubbing to yourself, your family and / or your companion animals.

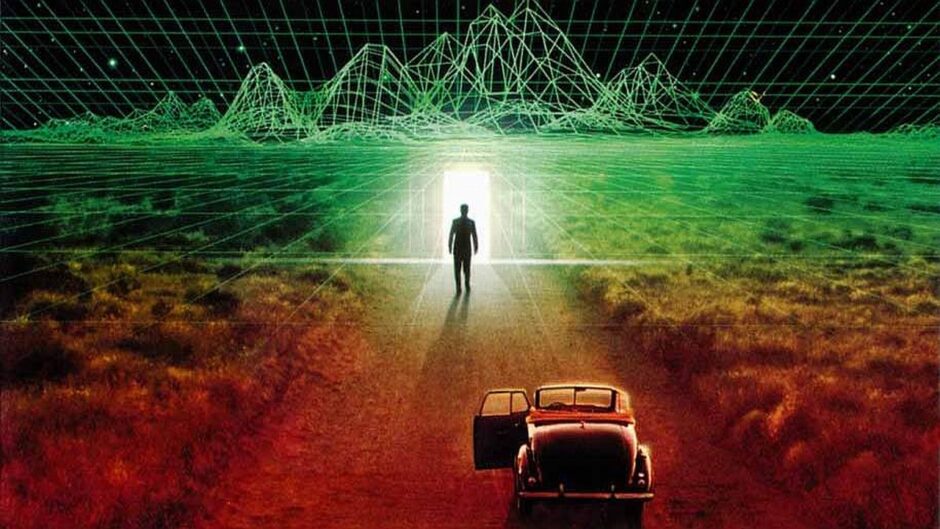

Although tearjerkers have been Hollywood’s secret sauce since the earliest “I want to be alone” Garbo movies, their heyday is considered to be the seventies and eighties. This time saw a plethora of cryfests like Terms of Endearment, The Way We Were, Love Story, Kramer vs Kramer, Field of Dreams, ET, Top Gun, Beaches, Watership Down, and A Star is Born (the Streisand/ Kristoffersen version) and many more, hit our screens. We cried. And cried. And cried some more. It was magnificent. Not a dry eye in any house. Then peak tears arrived in 1997 with the titan of them all, the blockbuster Titanic, and we gave our tear ducts a rest. However, it seems there are stirrings in the wind that it might just be crying again[1]. Oh yeah, baby, yeah.

The article got me pondering my all-time, guaranteed to open the emotional floodgates films. I blubbed my way through all of the above and many more. But if I want to cry without resorting to watching a movie— if I were an actor getting myself into the zone—there are two standouts. Curiously, both are children’s films, and both are about animals. So … drum roll … at the pinnacle of my all-time weepies? The 1994 film of Black Beauty. Specifically, the bit when Beauty sees Ginger for the last time alive.

“As if by magic, there she was, my beautiful Ginger. She was skin and bones. What had they done to her?”

From the 1994 film Black Beauty

They stand next to each other in a cab rank for a moment, and Beauty remembers when she was young and beautiful and all their happy ‘before times’ when men were kind. The next time he sees her, she is being hauled away, lifeless, on a cart. Tearing up as I write.

Black Beauty was my favourite book as a horse-mad little girl, which likely underpins my response to the film. I still have a copy. The last time I read it, I cried from about half way through, ending in convulsive sobbing at the bittersweet end . Luckily, it’s not a long book—I don’t think my internal waterworks could have coped.

Next? The ever-green Disney classic, Bambi. Specifically, the bit when a hunter shoots Bambi’s mother, and he’s left all alone. Gets me every time. In third place, Bambi again — when we realise his father is watching out for him. Now I’m crying as I write. It’s amazing that this 1942 movie still tears the heartstrings in a way many more recent ones don’t.

What are your favourites when you want a good cry? Here are a couple of handy top compilations of films, songs and books to get your give your tear ducts a workout. I don’t always agree with the selections, but each to their tearful own.

Anyway, must run. Off to my local cinema to catch Freud’s Last Interview. With a title like that, it’s bound to be a tearjerker!

[1] If films don’t do it for you, try this this gravelly Ray Charles, version of It’s Crying Time Again.